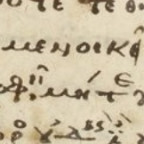

"On the Good King According to Homer" in Greek and Latin.

Not the most helpful for us, but posting here to provide an idea of the condition of the papyrus. You can take a look at the Greek text and see the are fragments at the beginning but a good amount of in relatively good shape.

Also:

23.1.Fish | Society for Classical Studies

Jeffrey Fish

www.baylor.edu

The Closing Columns of Philodemus’ ON THE GOOD KING ACCORDING TO HOMER, PHERC. 1507 COLS. 95-98 (= COLS. 40-43 DORANDI)

This article presents a reedition of the nal columns of Philodemus’ On the Good King According to Homer (columns 95-98 = cols. 40-43 Dorandi). In the nal…

www.academia.edu

Odysseus and the Epicureans

Odysseus was one of the classic role models for the Stoics. And he was my favorite mythological hero when I was a kid. Both excellent reasons for this…

howtobeastoic.wordpress.com