Thread

What Would Epicurus Say To Someone Who Complains "The World Is Unjust / Life Isn't Fair"?

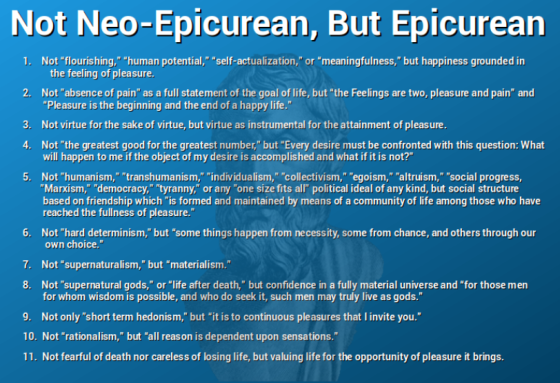

It came to my attention to day that there is another "Frequently Asked Ethical Question" to which we should have a thread presenting an answer in Epicurean terms. I will set up a FAQ question and link to this thread as well as to what develops into the most likely/consensus answer.

The Complaint/Question/Issue is generally stated in terms of "Is There No Justice In The World?" or "Life Isn't Fair!"

What would Epicurus say to such a person?

I think one reason we haven't seen that discussed much in…

The Complaint/Question/Issue is generally stated in terms of "Is There No Justice In The World?" or "Life Isn't Fair!"

What would Epicurus say to such a person?

I think one reason we haven't seen that discussed much in…

Cassius