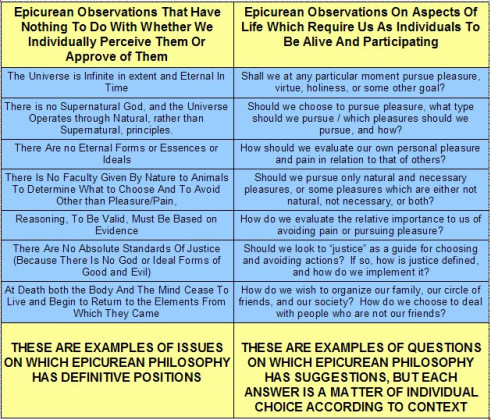

As I am working through transcribing the 1743 edition of Lucretius, I am also working on a table of topics under which to organize the references. I think most all of Lucretius can be summarized under one of the headings below, but there are innumerable ways to summarize. Here is my current highest-level list - I will constantly fine-tune so I would be interested in any comments:

Physics: The universe is Natural. As a whole it has existed eternally in time, it is infinite in extent, it operates by natural and not supernatural forces, it is neither centrally ordered or chaotic, and nothing exists which is not part of the natural universe.

Canonics: All that is relevant to us is perceived and judged through the evidence of our five senses, our feelings (pleasure and pain), and our anticipations. "Reason" has no relevance to us unless it is grounded in such evidence.

Ethics: Morality/ethics has meaning only to a living mind/spirit, and our mind/spirit ceases to exist at death. Pleasure is the guide of the living, and there are no absolute ethical standards set by supernatural gods or by ideal forms of virtue.