Welcome JMGuimas !

There is one last step to complete your registration:

All new registrants must post a response to this message here in this welcome thread (we do this in order to minimize spam registrations).

You must post your response within 72 hours, or your account will be subject to deletion. Please say "Hello" by introducing yourself and/or by telling us what prompted your interest in Epicureanism - and/or post a question.

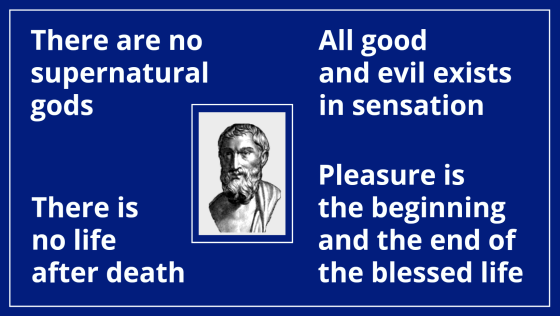

This forum is the place for students of Epicurus to coordinate their studies and work together to promote the philosophy of Epicurus. Please remember that all posting here is subject to our Community Standards / Rules of the Forum our Not Neo-Epicurean, But Epicurean and our Posting Policy statements and associated posts.

Please understand that the leaders of this forum are well aware that many fans of Epicurus may have sincerely-held views of what Epicurus taught that are incompatible with the purposes and standards of this forum. This forum is dedicated exclusively to the study and support of people who are committed to classical Epicurean views. As a result, this forum is not for people who seek to mix and match some Epicurean views with positions that are inherently inconsistent with the core teachings of Epicurus.

All of us who are here have arrived at our respect for Epicurus after long journeys through other philosophies, and we do not demand of others what we were not able to do ourselves. Epicurean philosophy is very different from other viewpoints, and it takes time to understand how deep those differences really are. That's why we have membership levels here at the forum which allow for new participants to discuss and develop their own learning, but it's also why we have standards that will lead in some cases to arguments being limited, and even participants being removed, when the purposes of the community require it. Epicurean philosophy is not inherently democratic, or committed to unlimited free speech, or devoted to any other form of organization other than the pursuit by our community of happy living through the principles of Epicurean philosophy.

One way you can be most assured of your time here being productive is to tell us a little about yourself and personal your background in reading Epicurean texts. It would also be helpful if you could tell us how you found this forum, and any particular areas of interest that you have which would help us make sure that your questions and thoughts are addressed.

In that regard we have found over the years that there are a number of key texts and references which most all serious students of Epicurus will want to read and evaluate for themselves. Those include the following.

- "Epicurus and His Philosophy" by Norman DeWitt

- The Biography of Epicurus by Diogenes Laertius. This includes the surviving letters of Epicurus, including those to Herodotus, Pythocles, and Menoeceus.

- "On The Nature of Things" - by Lucretius (a poetic abridgement of Epicurus' "On Nature"

- "Epicurus on Pleasure" - By Boris Nikolsky

- The chapters on Epicurus in Gosling and Taylor's "The Greeks On Pleasure."

- Cicero's "On Ends" - Torquatus Section

- Cicero's "On The Nature of the Gods" - Velleius Section

- The Inscription of Diogenes of Oinoanda - Martin Ferguson Smith translation

- A Few Days In Athens" - Frances Wright

- Lucian Core Texts on Epicurus: (1) Alexander the Oracle-Monger, (2) Hermotimus

- Philodemus "On Methods of Inference" (De Lacy version, including his appendix on relationship of Epicurean canon to Aristotle and other Greeks)

- "The Greeks on Pleasure" -Gosling & Taylor Sections on Epicurus, especially the section on katastematic and kinetic pleasure which explains why ultimately this distinction was not of great significance to Epicurus.

It is by no means essential or required that you have read these texts before participating in the forum, but your understanding of Epicurus will be much enhanced the more of these you have read. Feel free to join in on one or more of our conversation threads under various topics found throughout the forum, where you can to ask questions or to add in any of your insights as you study the Epicurean philosophy.

And time has also indicated to us that if you can find the time to read one book which will best explain classical Epicurean philosophy, as opposed to most modern "eclectic" interpretations of Epicurus, that book is Norman DeWitt's Epicurus And His Philosophy.

(If you have any questions regarding the usage of the forum or finding info, please post any questions in this thread).

Welcome to the forum!