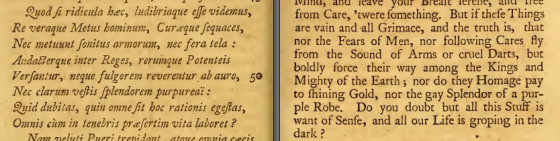

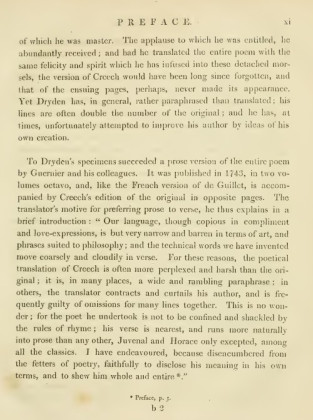

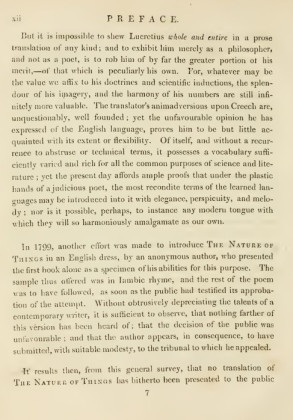

I have been looking for a long time for a side-by-side Latin-English translation of Lucretius, and searching Archive.org today I see for the first time one that I have never seen before. Does anyone know anything about this version? I can't even be sure who the translator is, but the introduction says that the Creech version was "many years ago" and this one is supposed to be more literal. Unfortunately it has the old "f" for "s" font style, but the eye adjusts to that pretty quickly, and the arrangement of the text does a pretty good job lining up the respective Latin and translated English. I've downloaded the PDF and I expect screen shots of this version will be helpful in the future. This provides the Latin and at least a starting point for translation, and then other translators (such as Smith) can be used to fill out the meaning. Thanks to Eoghan or I would not have found this!

Note: We really need the best public domian side-by-side Lucretius we can find for teasing out the meaning. I continue to look for an out-of-copyright version of the LOEB side by side edition from the 1920s, but I've not been able to find one on Archive.org or anywhere else. I watch this site (http://www.edonnelly.com/loebs.html) but they can't seem to find one either. If anyone has access to a library with an old collection of Loebs from which a PDF can be made of a public domain edition (not the more recent one which is copyrighted) then please post about it!

https://archive.org/stream/tlucret…age/n9/mode/2up