E.S. XXXVI (36) The life of Epicurus, when compared with that of other philosophers, seems almost legendary thanks to the calmness and self-sufficiency that distinguished him.

-----

In Mytilene, where once philosophical schools flourished, a young philosopher appeared with innovative thought on the study of Nature, through the epistemology of the Canon, or “On Criteria and Elements.” At first, he learned it from Nausiphanes, but he developed it far more, setting it against the endless dialectic of the other schools.

With a sparkle in his eyes, a proud gaze, a clear mind free from all fear, with a language that speaks with frankness and clarity, with a heart beating for friendship and a hand self-sufficient and generous in offering benefit, that young philosopher arrived in Mytilene and began to overturn the “recipe” of the idealistic soup of the other schools.

It was then, in Mytilene, that everything was at stake - even the very life of Epicurus. It was then that he began to make the most serious decisions of his life, when his presence provoked unrest and reaction; it was then that the dogmatic schools of endless dialectic and empty talk saw him as a threat and rose against him, shouting like a mob with the scorpion’s tail ready to strike:

Who is this who dares to teach us that the proper epistemology for the study of Nature is the Canon and not Dialectic, and to claim that everything around us is made of atoms and the void?

Who is this who dares to tell us that the soul is not immortal and that we shall not live forever?

Who is this who assures us that the gods are so blessed that they are indifferent to caring for us and our hypocritical, self-serving dealings?

Who is this who has the audacity to say that Nature contains swerve as the responsibility of freedom, and not only necessity, fate, destiny, and the inescapable doom?

And who is this libertine who speaks openly of pleasure and even connects it with eudaemonia?

Who is this, ehhh??

The dogmatists, through their metaphysical doctrines, were themselves transformed metaphysically, like the wild Poseidon pursuing Odysseus. Just before they rushed after Epicurus, nervously stepping on their long robes, and just before things took a dangerous turn, Epicurus put his Canon into practice: with sharpened senses, with preconceptions (well-founded knowledge from interaction with the environment), and with his emotions, he grasped the hostile intentions of the crowd and thought clearly:

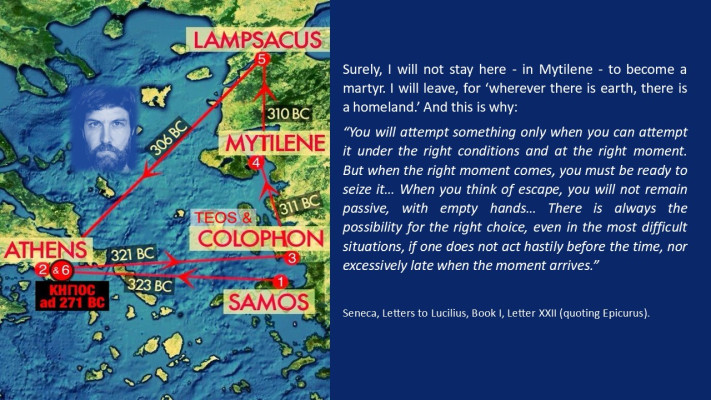

No way I will stay here - in Mytilene - to become a martyr. I will leave - wherever the earth, there my homeland. And this, because: “You will attempt something only when you can attempt it under the right conditions and at the right moment. But when the right moment comes, you must be ready to seize it… When you think of escape, you will not remain passive, with empty hands, because there is always the possibility of the right choice, even in the most difficult situations, if one does not act hastily before the time, nor too late when the moment arrives.”

Thus, at the right moment or as the Greeks called it, kairos, meaning “the opportune time which, alas, if you let it pass, is lost” - he made the “swerve of the swerve” and departed elsewhere, to develop his philosophy among people with open minds, capable of enduring the search into the reality of phenomena and their causes. So capable, indeed, that they could correct him where he erred, and this correction gave him the greatest joy!

Thus, he boarded the first ship he found before him and left. But it was a day when the sea grew wild and a great storm broke out. The vessel he was on was shattered, the waves struck him mercilessly, and he found himself struggling in the waters. As Diogenes of Oenoanda recounts: Epicurus was gravely injured, swallowed seawater, was scraped against the rocks; his body was covered in wounds. With toil and pain he swam, until a wave brought before him a crafted material of nature, made with care by some artisan: a wooden table floating among the wreckage. Wounded and exhausted, he managed to cling to it and reach a rocky ledge, where he remained for two whole days. And in the end, when he was saved, scientific thought itself was saved - the thought that liberates humankind from the chains of Lethe - oblivion.

That table which saved him did not remain in his mind and soul as merely a piece of wood; he transformed it into the table of dialogue, the place where he would sit with his friends to discuss, separating, in the Greek worldview, the chaff from the wheat - how Nature truly works, and how we may live, in the little span of our life, pleasurably within it. It became the table where food was shared with friends, because, as he himself said: “Whoever eats alone, eats like a wolf.”

The table became a symbol of friendship and science; there were heard voices unafraid, open eyes that did not imprison Nature in boxes with labels, but let her reveal herself through her own laws, manifest her own functions, be investigated and discovered through her own forces, speaking in her own beautiful language, filled with the light-phὸs of photons.

That small table of survival became the great table of the Garden, where philosophy did not remain at “empty words of affection,” but became practice - and science, a way of life. There knowledge was no longer theory for theory’s sake, but the transmission and response of the open and fearless mind to experience. There friendship was revealed as the greatest good, and science as the tool of freedom and serenity. Thus, the table that saved him from the storm became the table that saves humanity from fear, dogmatism, arrogance, and superstition.

From this trial in Mytilene began the spread of the epistemology of the Canon with Physics, and he reached Lampsacus, where he met most of the true friends of his life, and finally, together with them, founded in Athens his philosophical School called the Garden. There dialectic proved misleading; the gifts of Nature - the senses, the preconceptions, and the feelings - are the criteria of truth; atoms and the void, the foundation of Nature; knowledge, condensed into clear terms, avoiding endless rhetoric with “empty words” and “hollow phrases.” True knowledge is not merely the imposition of mind upon Nature, but also the response of the open and fearless mind to the powers and capacities with which Nature herself has endowed us.

Centuries later, from that Garden, the same thought passed to Lucretius, who with his masterpiece De Rerum Natura carried Epicurean epistemology into Rome and turned it into the poetry of Nature. In the Middle Ages it was lost, buried under dogmatism and superstition, but in the seventeenth century it revived once more, when the natural philosophers of the Enlightenment built upon this empirical method.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Epicurean hypothesis of atoms and the void was confirmed, reaching into particle physics, quantum theory, and nuclear energy. Trust in the senses and in experiment became the foundation of technology: from medicine and vaccines to computers and the internet. Even Epicurus’ multivalued logic is reflected today in probabilistic methods, in statistics, in machine learning, in quantum computing that surpasses the “either 0 or 1” of Aristotelian logic.

In the twenty-first century, the epistemology of the Canon is triumphantly verified. Science shows us how to live: with health, with freedom, with serenity, with friendship. For from the beginning, Epicurus’ philosophy was not meant to impress, but to benefit. From the table of shipwreck in Mytilene to the tables of modern physics laboratories, the same method continues: trust in the investigation of Nature with sober reasoning, avoidance of fear, knowledge that leads to benefit and well-being. And thus, to this day, science evolves: it takes theories, tests them, improves them, and transforms them into something more fruitful and more beneficial.

A Parallel: Ithaca and the Garden

And here, a parallel arises spontaneously: in contrast to Odysseus, who begins his journey with companions and loses them all until he arrives alone in Ithaca, Epicurus begins alone and ends in the Garden surrounded by true friends. Of course, there are two exceptions who chose to leave and become adversaries - perhaps unable to endure atoms, the void, and the Canon, preferring instead the illusions of Plato’s Dialectic. And there was also the natural loss of Metrodorus of Lampsacus, the beloved friend who died before Epicurus and caused him deep sorrow - a sorrow that did not erase the memory of friendship but made it shine even brighter. Thus, the Garden flourished as a community of true friends with open minds and pure hearts.

While Odysseus’ companions were transformed into swine - that is, into shipwrecks of their own lives - Epicurus’ friends proved that with the right choices life is not a shipwreck, but a precious gift; and true friendship is salvation.

Odysseus and Nature

Odysseus was punished by the forces of Nature because at the beginning he stood against her with arrogance. He may have survived with disguises, cunning, and stratagems; but he could not see Nature as an indifferent power that simply unfolds. He provoked her, shouting his name to Polyphemus, as if to say to Nature: “Do you know who I am? I am the one who destroyed Troy.” And so the sea became punishment. Nature, indifferent yet relentless, cast him into endless wandering. The first Greek, Odysseus, studied Nature as an adversary, and for that he remained captive to hubris until he reached catharsis and was liberated.

Epicurus and Nature

Epicurus, when tested by the raging waves as he fled from Mytilene, did not see Nature either as hostile or with arrogance. The ship was shattered, and he was saved by a simple wooden table that floated. His salvation was not a stratagem, but a chance gift of Nature - and he accepted it with clarity. For Epicurus, Nature is indifferent: neither loving nor hating, she simply moves. And this movement, as he reflected upon that rock, must be studied rightly, with foresight of stormy winds, so that even “meteorology” might be born and evolve.

Odysseus provoked Nature, and he was punished. Epicurus accepted her exactly as she is, and he was saved. The first is intelligent in survival, yet captive to hubris until he is redeemed. The second is intelligent in life, for he did not provoke, having already found the treasure of self-sufficiency, freedom, and friendship, until the end of his days.

Thus, it is revealed: Epicurus studied Nature rightly, not as an adversary nor as a friend, but as an indifferent reality - yet respectful, when she gives us the data by which we may live in serenity.

For if we wish to see things more clearly in the philosophical and epistemological sense, we may understand that Ithaca for Odysseus is not simply a symbol of return, but of battle with the suitors; not merely the end of a journey, but the continuation of the struggle of opposites - an endless dialectic that brings no true peace, for it leads to necessities, and ultimately the question becomes: who possesses the greater power. Odysseus reaches Ithaca only to end with a faithful Penelope who did not even recognize him, weaving at her loom and unraveling what she wove - a life of “weave and unweave, endless toil.” This is the endless dialectic.

But the harshest truth of life, which also reveals Homer’s mastery, is this: to return to your home and kingdom, and to be recognized only by your dog. Argos recognizes Odysseus not by words nor by deeds, but only by his scent. “I know you because I smell you.” This is the most faithful moment of recognition, which vanishes immediately, for the dog dies at once. In short, recognition comes from an animal and not from humans. The truest moment turns into poetic irony: loyalty exists, but cannot be acknowledged, for before Odysseus stand yet more battles. This is the endless dialectic.

The Garden of Epicurus, by contrast, is not a battlefield nor a loom that unravels what it weaves. It is the journey and the destination without losses; there one does not need to be recognized by a dog through scent, for there are friends who recognize you from beginning to end by your face and your true identity. There life is not “weave and unweave,” but a common table with real work, in dialogues with clarity, with genuine vision, and with the right strategic art of living that culminates in eudaimonia. This is the Canon.

Odysseus, generally and specifically, is the man of masks. In his course from Troy to Ithaca he becomes “Nobody” to survive, a “beggar” in Ithaca to endure, a “king” by name to reclaim power. His intelligence is indeed strategic, but psychologically he resembles the man who cannot bear to stand naked before Nature; he needs masks to control his image, to test his relations, to confirm his worth. His masks are the camouflage of the warlord, who sees Nature metaphysically, and therefore must hide from her. For in the course of his journey his companions were lost and he remained utterly alone - and thus the catharsis of liberation had not yet arrived.

So, when does the catharsis of liberation begin for the Greek Odysseus? Here unfolds the unparalleled mastery of our poet, Homer: Odysseus, before two women - forces of Nature - reaches full self-awareness and knowledge of himself, and pronounces, as a noble Greek: With Circe–Nature he will not surrender to reckless pleasures, for he has understood they lead to destruction; he transforms them into refined pleasures. And with Calypso–Nature he will stand bravely and confess: “No, I cannot become immortal, because I am not immortal”! So human, all too human - as Nietzsche titled one of his books.

Psychology shows us that the man who hides behind identities, titles, and honors is captive to insecurity and to his inner void when he is or feels alone. Odysseus cannot bear to leave Polyphemus without shouting his name; he thirsts for recognition, even if it costs him Poseidon’s curse. And Poseidon’s curse is nothing but the hubris of arrogance against Nature, against an entire City and its Inhabitants - for whoever sows winds scatters storms. It is no accident that Homer places him in adventures after the conquest and destruction of Troy; the Trojan Horse, Odysseus’ work, brought the final outcome and the total destruction of a city and its people. This fact is hubris, and the adventures that follow function as catharsis: you provoked pain and hubris? This is paid with pain. The need for external validation leads to new battles, new losses, and a long journey through trials, until once again the boundary is found that protects man from arrogance before Nature.

Epicurus, by contrast, has no need of masks. From the beginning he is who he is, with name and identity. He does not hide, does not disguise himself, does not play with personae. He does not need to be recognized as leader, guide, or king-philosopher. His philosophy is marked by clarity, for he speaks simply and plainly about the limits between pain and pleasure. Here lies prudent measure: the innate good may be pleasure, but the goal is not momentary enjoyment - it is eudaimonia. Without justice, beauty, and prudence there is no pleasant life; and without a pleasant life there is no justice, beauty, or prudence.

In this simplicity emerges the treasure of freedom: self-sufficiency that is not deprivation, but inner wealth and strength, the power to continually create space for the other beside you. Such a treasure of self-sufficiency and freedom Epicurus discovered, and for this reason he did not need to hide behind identities nor seek recognition through masks and personae. His very life was his work; his friendship and gratitude toward his friends were the recognition of those who stood beside him until his last breath.

Where Odysseus plays with masks and roles in order to survive, Epicurus stands with the clarity of his face in order to live. Where Odysseus is clever, Epicurus is Wise; cleverness may be a tool of survival, but wisdom is the foundation of a whole life. Odysseus saves himself from Polyphemus’ cave, confronting the tragic nature of existence as his companions are lost one by one to the forces of Nature; Epicurus, by contrast, saves humankind from fear and delusion, for with friendship and prudence man does not feel existential emptiness nor fear the forces of Nature. He feels security and trust in the help of a friend when needed, and thus sees his friends as equals - blessed, wise, and psychophysically whole.

And here emerges the recent irony of ironies: some politician - a name that needs no introduction - wrote a book entitled “Ithaca”, as if he had returned from an epic, while in truth he merely returned from his great delusions, to which he continually goes back.

But Pericles said it in his Funeral Oration, as Thucydides preserved it, did he not? “Athens is the spiritual center of Greece; here the individual is a complete citizen with manifold action; the city is greater than its reputation and is acknowledged even by enemies and subjects. Proofs and witnesses of the glory of our city will inspire admiration in contemporaries and in posterity, while the praises of poets or prose-writers, like Homer, are useless and harmful. For in defense of this city, men unshakable in courage fought their battles. And this remains the solemn responsibility of those who survive: to honor them by guarding the city with the same indomitable spirit.”

So what use is Homer’s Ithaca, when as a politician you sank the city and its citizens into illusions - illusions you sowed like seeds in barren soil, which sprouted at last as thorns: vain hopes, cowardice, and weakness?

One conclusion stands clear: Marx’s dialectic materialism and the necessities of ideologies and obsessions consumed his mind as well. All sit at the table of idealism, laden with dishes of “dialectic,” and they eat it as if it were a luxurious banquet: appetizer, main course, and dessert. They think they are nourished healthily and filled, while in reality they consume canned food full of preservatives and scurvy - nourishment that brings not life, but decay and sickness. Nothing innovative, nothing fresh, no self-born knowledge! Only the same things repeated, chewed over like goats!

They imagine they taste the fine dish of Aristotelian dialectic of the excluded middle; but the food is bland and tasteless, for it always gets stuck in the details of particulars, never offering the clear General Picture of tangible reality and of politics, which is the “Art of the Possible Real.” And thus, they end up in dilemmas: either white or black, like a chessboard that knows no other colors.

The Ballot and the Placebo of Illusions

The same tasteless food is served in this weary land to the man next door, presented as supposedly healthy truth - something that looks like fruit, but inside is hollow, like an empty pomegranate that shatters in your hands. The man next door, who always holds the losing card, is the very one who, in the end, is punished for all misfortunes by the slaps of life.

For when the hour of great responsibility arrives, the vote, those holding the losing card go and choose not true statesmen but petty politicians, charlatans of illusion, who promise miracle cures. Yet what they offer are not even generic medicines; they are mere placebo pills, candies disguised as therapy, which end up becoming antidepressants. And the modern Greeks consume antidepressants like sweets from the kiosks, believing they sweeten life, while in reality they numb the soul and the mind, leaving them unable to discern what harms and what benefits us in this land, at last?

It is now a fact in Greece, as friends who are doctors and pharmacists have confirmed to me, that the prescription and distribution of antidepressants have exploded, placing the country among the highest in Europe. “Bravo to us. And cheers to our bitter wine…”

So listen, you Pseudo-Odysseus: lounge now in your pseudo-Ithaca, with your little Penelope, mourn your dead dog, eat your fat parliamentary pension, while you remain untouched in the sanctuary of impunity, protected by the law on ministerial responsibility. Aidōs, Argives - enough already!

Elli Pensa

10th November 2025

Comments 1