The Uncertainty of Science and the Certainty of Faith

By Dimitris Altas, cardiologist and member of the Analysis and Experiential Application Team of Epicurean Philosophy Today [(http://www.epicuros21.gr)]

What is knowledge, and what is faith? One might say that they represent two entirely different perspectives on Reality or Truth. And here comes the next question: Are reality and truth identical? The answer given by a scientist would most likely differ from that of a person of faith!

For a scientist, reality is approached through solid knowledge, which initially relied solely on experience and observation of nature and later on experimental verification and the inability to refute—that is, confirmation and non-contradiction, terms first introduced by Epicurus in his famous Canon, which thereafter formed the foundation of the scientific method for exploring the Nature of Things.

This solid knowledge can either be timelessly indisputable and fully verifiable, such as the fact that the Earth is round and revolves around the Sun, or currently undisputed and not disproven based on available evidence, such as the theory of evolution, the theory of relativity, and the principles of quantum mechanics.

Theories: Scientific Uncertainty and the Acceptance of Knowledge

Scientific theories are proposed explanations for natural phenomena, for which the scientific community "suspends judgment" until clear evidence or the inability to refute them establishes them as solid knowledge.

Thus, the duty of the scientific community is always to attempt to disprove a proposed theory, not out of competitiveness or skepticism, but as a fundamental part of the scientific process.

Only the inability to disprove a theory elevates it to solid knowledge, always with the caution that this may be overturned in the future. As Carlo Rovelli points out, "Science is not reliable because it offers certainty. It is reliable because it provides the best answers we have at the moment."

The phrase "suspending judgment" comes from the Skeptic philosopher Pyrrho and means withholding judgment on a subject until more undeniable evidence allows acceptance or rejection of it. This was a major contribution of ancient Skeptic philosophy to scientific thought and was later incorporated by Epicurus into his Canon.

Of course, radical Skeptics permanently suspend judgment, doubting everything around them, whereas Epicurus places things on a solid foundation.

Accepting a scientific theory does not necessarily mean that a previously existing theory interpreting the same phenomenon is automatically rejected. Often, a new theory expands the scope of an older one and deepens the understanding of a phenomenon’s causes. For example, both quantum mechanics and relativity extend Newtonian theory—quantum mechanics applies in the microscopic world of quanta, while relativity applies in the vast macrocosm of the universe—despite their apparent contradictions.

Even though many assumptions of Newtonian physics are overturned by these newer theories, Newtonian mechanics still excellently describes the world on human-scale dimensions and remains the foundation of existing technology.

Furthermore, quantum mechanics, which experimental data imposed against human experience and conventional logic, has countless technological applications in the modern world, which validate it as solid knowledge—despite the fact that it remains largely incomprehensible!

The documentation and value of scientific knowledge for human societies lie in its applicability to technology. The knowledge of agriculture and metallurgy elevated humanity from nomadic foraging to settled farming, leading to the formation of societies—with all the implications that brought—and, for the first time, to a surplus of food. This surplus necessitated storage and management, ultimately driving the development of mathematics.

The historical evolution of societies reflects the advancement of technology—shaping their structures, values, wealth, prosperity, and position in the global system.

As scientific knowledge expands and technology continually advances, it serves as evidence that humanity is capable of understanding the real world—perhaps not in its entirety, but progressively. If a deeper truth exists, it resembles the horizon: the closer we approach, the farther it recedes. Yet, the horizon itself is merely an illusion—and this is solid knowledge!

The fact that we cannot illuminate the entirety of reality does not mean that we know nothing! The binary way of thinking—either “I know” or “I do not know”—reflects the two-valued logic first introduced by Parmenides of Elea in his famous poem On Nature. In it, Parmenides speaks of two paths: the path of truth (of being), which is accessible, and the path of deception (of non-being), which is impassable. While acknowledging that human opinions contain both truth and illusion, he categorizes them under the path of deception.

Socratic dialectic and the so-called maieutic method are based on the two-valued logic of Parmenides, which was taught to Socrates by his student, Zeno of Elea.

As dialectic, in the famous Platonic dialogues, it leads to contradictions and dilemmas, proving that Socrates’ interlocutor is unaware of their own ignorance on the subject. In contrast, Socrates is considered wiser because he is aware of his ignorance! As for the maieutic method, all it reveals is the ignorance of Socrates’ interlocutor—rather than arriving at a clear definition of the concept under discussion, which is the essential goal.

Epicurus tells us that this is expected—because absolute concepts and perfect definitions do not exist. Nature does not operate on binary logic (black-and-white), but rather on the logic of shades of gray (multi-valued logic). We cannot define a concept in absolute terms—we can only describe it.

In nature, the concepts of “absolute” and “perfect” are empty; nature is incomplete and constantly evolving. And when it comes to knowledge of reality, it is necessary to the extent that it helps us understand the world in a sufficiently satisfactory way—so we can discard the fear of the unknown and live a peaceful and pleasurable life!

That is the essence of knowledge.

The Truth, for the believer, is one, timeless, and absolute, and is not approached through any form of inquiry. Truth is revealed by God, the Prophet, the Leader, or the Guru to the faithful, and comes packaged with a moral code of conduct and a way of life that allows no questioning or negotiation.

The clergy of religion or ideology interprets the scriptures and guides the faithful, who are the chosen ones among the misguided. They hold a sacred duty to enlighten others and lead them to the righteous path by any means—or, if they refuse, to simply eliminate them—so that humanity may reach an ideal society of unanimity.

The slightest deviation from the clergy’s interpretation is considered a mortal sin and is punished exemplarily.

Believers do not demand proof, nor do they subject their faith to the test of logical reasoning. They do not question whether what they are asked to believe aligns with their personal experience or daily reality.

They believe that the dead can be resurrected, despite common sense and the collective experience of humanity! They enjoy feeling chosen by God or the Leader and are willing to endure any sacrifice or take any action they believe will please their object of worship. Of course, they expect something in return—whether it is a place in Paradise in the afterlife (as in monotheistic religions), or a prestigious position in the political party or government, from which they can experience the pleasure of wielding power (an unspoken desire of many believers).

Unlike science, faith offers certainty in its irrationality. It does not require believers to strain their brains in search of answers—they are handed down through Revelation. Faith does not need Reason—it needs Emotion. For believers, the million-year evolution of the human neocortex is wasted time!

And since "whoever is not with us is against us," there is never any room for negotiation when it comes to ideology. It is no coincidence that the bloodiest wars in human history have been religious, and that the greatest crimes against humanity have always stemmed from ideological or religious origins.

Take, for example, the three monotheistic religions—which, throughout history, has been the most violent? How many crimes have been committed, and continue to be committed, in the name of Christian "Love," the Prophet, or Jehovah?

Take, for example, the Nazis or Pol Pot’s regime in Cambodia. Consider the Armenian and Pontic Greek genocides committed by the Turks. Yes, there have always been pragmatic reasons—geopolitical, economic, and others—but those in power have consistently relied on religious and ideological fanaticism to manipulate the masses and drive them to crimes and bloodshed.

The Holocaust, carried out by the Nazis against the Jewish people, was purely a matter of ideological obsession. And the recent genocide of Palestinians in Gaza traces its roots back to the Bible and the supposed divine promise to the Jewish people for exclusive possession of the land of Palestine. In the end, the greatest "miracle" of faith is its ability to transform peaceful, everyday people into ruthless criminals.

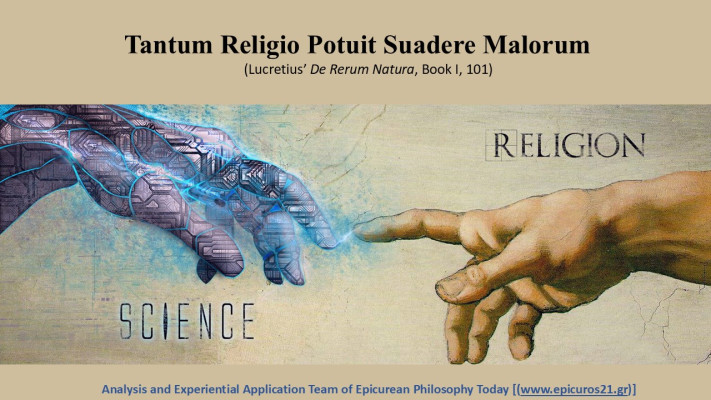

The true historical conflict throughout humanity’s course has been the battle between ideology and knowledge. While the former sought to impose its "Truth," the latter strived to understand the world.

Applied science and technology, beyond promoting human prosperity, have also been used against humanity—and today, they even possess the power to annihilate it. Throughout history, they have always served as tools in the geopolitical and ideological-religious struggle for dominance. Science, like all human endeavors, has its dark side.

However, whatever hope remains for humanity’s survival lies solely with people of Knowledge—those who stand firmly on the ground of reality rather than floating in ideological clouds. Their ethics emerge from the needs of real life, rather than being imposed from above by a god or leader. They filter everything through the sieve of logical analysis and often "suspend judgment" to better investigate the evidence.

Science holds no certainties—it always doubts, researches, reexamines, and updates knowledge. It is ever-learning—because learning is the daughter of doubt. Beyond what has already been mentioned, science cultivates a culture of negotiation and compromise. When one does not claim absolute truth, they are willing to listen and perhaps even acknowledge part of another's truth. Interests can be negotiated—ideologies never can!

This culture characterizes the Ancient Greek spirit. It is no coincidence that the Ancient Greeks elevated rhetoric and argumentation to the highest art, aiming for persuasion through reason. As Adam Watson highlights, justice among the Hebrews, as a measure of Divine Law, is blind and uncompromising—it must be enforced, even if the sky itself threatens to fall. Among the Greeks, "Dike" (Justice) takes into account commonly acknowledged fairness, the status quo, and negotiation—assisted by a mutually accepted mediator, with the clear purpose of keeping the sky in its rightful place.

December 24, 2023

Comments 3