The following is a list of citations to Epicurean texts which are relevant to understanding Epicurus' view of justice and relations among both communities and individuals. Emphasis here is on statements which would likely be viewed as controversial and/or impolitic in the modern world, yet must nevertheless be considered if we want to understand the ancient Epicurean mindset:

Epicurus PD10: (As to the invalidty of considering something monstrous if it allows the person involved to successfully live pleasurably) "10. If the things that produce the pleasures of profligate men really freed them from fears of the mind concerning celestial and atmospheric phenomena, the fear of death, and the fear of pain; if, further, they taught them to limit their desires, we should never have any fault to find with such persons, for they would then be filled with pleasures from every source and would never have pain of body or mind, which is what is bad."

Diogenes Laertius: (as to some men being our enemies) "Epicurus used to call ... the Cynics the 'enemies of Greece"

Diogenes Laertius: "He [the wise man] will be more susceptible of emotion than other men: that will be no hindrance to his wisdom. However, not every bodily constitution nor every nationality would permit a man to become wise."

Diogenes Laertius - Will of Epicurus (As to his wealth) And from the revenues made over by me to Amynomachus and Timocrates let them to the best of their power in consultation with Hermarchus make separate provision for the funeral offerings to my father, mother, and brothers, and for the customary celebration of my birthday on the tenth day of Gamelion in each year, and for the meeting of all my School held every month on the twentieth day to commemorate Metrodorus and myself according to the rules now in force. Let them also join in celebrating the day in Poseideon which commemorates my brothers, and likewise the day in Metageitnion which commemorates Polyaenus, as I have done previously.

Diogenes Laertius - Will of Epicurus (As to his owning slaves, and not freeing all at his death) "Of my slaves I manumit Mys, Nicias, Lycon, and I also give Phaedrium her liberty."

Diogenes Laertius- Will of Epicurus (As to his instructing that a child of a member of the school should marry within the school) - "And let Amynomachus and Timocrates take care of Epicurus, the son of Metrodorus, and of the son of Polyaenus, so long as they study and live with Hermarchus. Let them likewise provide for he maintenance of Metrodorus's daughters so long as she is well-ordered and obedient to Hermarchus; and, when she comes of age, give her in marriage to a husband selected by Hermarchus from among the members of the School."

Diogenes Laertius- (As to Epicurus disapproving of communism) - "He further says that Epicurus did not think it right that their property should be held in common, as required by the maxim of Pythagoras about the goods of friends; such a practice in his opinion implied mistrust, and without confidence there is no friendship."

Diogenes of Oinoanda: (as to making generalizations about cultural groups) :

"A clear indication of the complete inability of the gods to prevent wrong-doings is provided by the nations of the Jews and Egyptians, who, as well as being the most superstitious of all peoples, are the vilest of all peoples."

Diogenes of Oinoanda: (as to considering false religion to be a disease coexisting with the idea of love of humanity) "Now, if only one person or two or three or four or five or six or any larger number you choose, sir, provided that it is not very large, were in a bad predicament, I should address them individually and do all in my power to give them the best advice. But, as I have said before, the majority of people suffer from a common disease, as in a plague, with their false notions about things, and their number is increasing (for in mutual emulation they catch the disease from one another, like sheep) moreover, [it is] right to help [also] generations to come (for they too belong to us, though they are still unborn) and, besides, love of humanity prompts us to aid also the foreigners who come here."

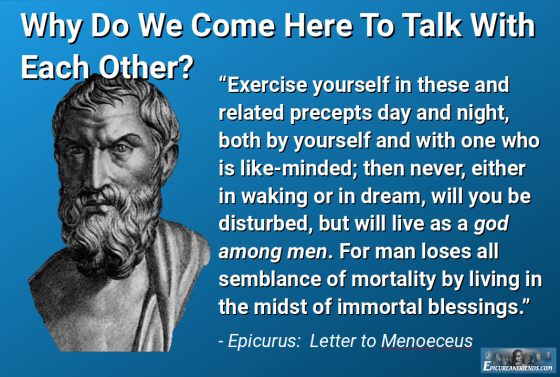

Epicurus Letter to Menoeceus: (As to the best life being spent among like-minded friends) "Exercise yourself in these and related precepts day and night, both by yourself and with one who is like-minded; then never, either in waking or in dream, will you be disturbed, but will live as a god among men. For man loses all semblance of mortality by living in the midst of immortal blessings."

Epicurus Doctrines on Justice (following PD10 that there is no absolute standard of right and wrong other than the pleasurable living of the people involved, so that when there is no agreement, there is no concept of justice):

- 32. Those animals which are incapable of making binding agreements with one another not to inflict nor suffer harm are without either justice or injustice; and likewise for those peoples who either could not or would not form binding agreements not to inflict nor suffer harm.

- 33. There never was such a thing as absolute justice, but only agreements made in mutual dealings among men in whatever places at various times providing against the infliction or suffering of harm.

- 34. Injustice is not an evil in itself, but only in consequence of the fear which is associated with the apprehension of being discovered by those appointed to punish such actions.

- 36. In general justice is the same for all, for it is something found mutually beneficial in men's dealings, but in its application to particular places or other circumstances the same thing is not necessarily just for everyone.

- 37. Among the things held to be just by law, whatever is proved to be of advantage in men's dealings has the stamp of justice, whether or not it be the same for all; but if a man makes a law and it does not prove to be mutually advantageous, then this is no longer just. And if what is mutually advantageous varies and only for a time corresponds to our concept of justice, nevertheless for that time it is just for those who do not trouble themselves about empty words, but look simply at the facts.

- 38. Where without any change in circumstances the things held to be just by law are seen not to correspond with the concept of justice in actual practice, such laws are not really just; but wherever the laws have ceased to be advantageous because of a change in circumstances, in that case the laws were for that time just when they were advantageous for the mutual dealings of the citizens, and subsequently ceased to be just when they were no longer advantageous.

(As to excluding from our lives people who cannot coexist with us):

39. The man who best knows how to meet external threats makes into one family all the creatures he can; and those he can not, he at any rate does not treat as aliens; and where he finds even this impossible, he avoids all dealings, and, so far as is advantageous, excludes them from his life.

(As to the desirability of being able to defend ourselves by force from threats against us, and living among people who share our values)

40. Those who possess the power to defend themselves against threats by their neighbors, being thus in possession of the surest guarantee of security, live the most pleasant life with one another; and their enjoyment of the fullest intimacy is such that if one of them dies prematurely, the others do not lament his death as though it called for pity.

Epicurus Letter to Menoeuces: (As to the best life as one being spent among -like-minded friends): "Exercise yourself in these and related precepts day and night, both by yourself and with one who is like-minded; then never, either in waking or in dream, will you be disturbed, but will live as a god among men. For man loses all semblance of mortality by living in the midst of immortal blessings."

Torquatus / Cicero: (As to some men being non-reformable and thus requiring restraint by force: "Yet nevertheless some men indulge without limit their avarice, ambition and love of power, lust, gluttony and those other desires, which ill-gotten gains can never diminish but rather must inflame the more; inasmuch that they appear proper subjects for restraint rather than for reformation."

Torquatus / Cicero: (As to the "safety of our fellow citizens" and defending our country in time of war can be essential to our own wellbeing) "Can you then suppose that those heroic men performed their famous deeds without any motive at all? What their motive was, I will consider later on: for the present I will confidently assert, that if they had a motive for those undoubtedly glorious exploits, that motive was not a love of virtue in and for itself.—He wrested the necklet from his foe.—Yes, and saved himself from death. But he braved great danger.—Yes, before the eyes of an army.—What did he get by it?—Honor and esteem, the strongest guarantees of security in life.—He sentenced his own son to death.—If from no motive, I am sorry to be the descendant of anyone so savage and inhuman; but if his purpose was by inflicting pain upon himself to establish his authority as a commander, and to tighten the reins of discipline during a very serious war by holding over his army the fear of punishment, then his action aimed at ensuring the safety of his fellow citizens, upon which he knew his own depended."

Lucian - "Aristotle the Oracle-Monger" (as to Epicureans confronting false religion) - ""The prosperity of the oracle is perhaps not so wonderful, when one learns what sensible, intelligent questions were in fashion with its votaries. Well, it was war to the knife between him and Epicurus, and no wonder. What fitter enemy for a charlatan who patronized miracles and hated truth, than the thinker who had grasped the nature of things and was in solitary possession of that truth? As for the Platonists, Stoics, Pythagoreans, they were his good friends; he had no quarrel with them. But the unmitigated Epicurus, as he used to call him, could not but be hateful to him, treating all such pretensions as absurd and puerile."

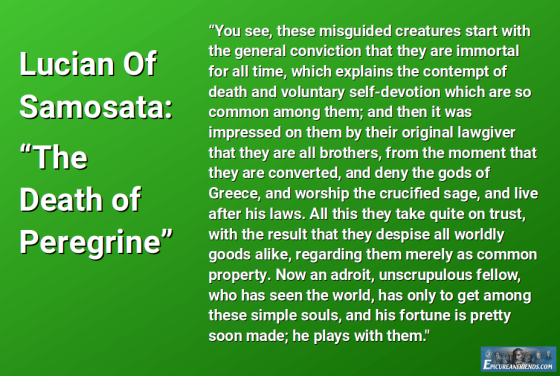

Lucian - "The Death of Peregrine" (as to Epicurean criticism of Christianity) - "It was now that he came across the priests and scribes of the 11 Christians, in Palestine, and picked up their queer creed. I can tell you, he pretty soon convinced them of his superiority; prophet, elder, ruler of the Synagogue--he was everything at once; expounded their books, commented on them, wrote books himself. They took him for a God, accepted his laws, and declared him their president. The Christians, you know, worship a man to this day,--the distinguished personage who introduced their novel rites, and was crucified on that account. Well, the end of it was that Proteus was arrested and thrown into prison. This was the very thing to lend an air to his favourite arts of clap-trap and wonder-working; he was now a made man. The Christians took it all very seriously: he was no sooner in prison, than they began trying every means to get him out again,--but without success. Everything else that could be done for him they most devoutly did. They thought of nothing else. Orphans and ancient widows might be seen hanging about the prison from break of day. Their officials bribed the gaolers to let them sleep inside with him. Elegant dinners were conveyed in; their sacred writings were read; and our old friend Peregrine (as he was still called in those days) became for them "the modern Socrates." In some of the Asiatic 13 cities, too, the Christian communities put themselves to the expense of sending deputations, with offers of sympathy, assistance, and legal advice. The activity of these people, in dealing with any matter that affects their community, is something extraordinary; they spare no trouble, no expense. Peregrine, all this time, was making quite an income on the strength of his bondage; money came pouring in. You see, these misguided creatures start with the general conviction that they are immortal for all time, which explains the contempt of death and voluntary self-devotion which are so common among them; and then it was impressed on them by their original lawgiver that they are all brothers, from the moment that they are converted, and deny the gods of Greece, and worship the crucified sage, and live after his laws. All this they take quite on trust, with the result that they despise all worldly goods alike, regarding them merely as common property. Now an adroit, unscrupulous fellow, who has seen the world, has only to get among these simple souls, and his fortune is pretty soon made; he plays with them."

Lucretius Book Four (Bailey) (As to willingness to use coarse / mocking descriptive personal characterizations) "And one man laughs at another, and urges him to appease Venus, since he is wallowing in a base passion, yet often, poor wretch, he cannot see his own ills, far greater than the rest. A black love is called ‘honey-dark’, the foul and filthy ‘unadorned’, the green-eyed ‘Athena’s image’, the wiry and wooden ‘a gazelle’, the squat and dwarfish ‘one of the graces’, ‘all pure delight’, the lumpy and ungainly ‘a wonder’, and ‘full of majesty’. She stammers and cannot speak, ‘she has a lisp’; the dumb is ‘modest’; the fiery, spiteful gossip is ‘a burning torch’. One becomes a ‘slender darling’, when she can scarce live from decline; another half dead with cough is ‘frail’. Then the fat and full-bosomed is ‘Ceres’ self with Bacchus at breast’; the snub-nosed is ‘sister to Silenus, or a Satyr’; the thick-lipped is ‘a living kiss’. More of this sort it were tedious for me to try to tell. But yet let her be fair of face as you will, and from her every limb let the power of Venus issue forth: yet surely there are others too: surely we have lived without her before, surely she does just the same in all things, and we know it, as the ugly, and of herself, poor wretch, reeks of noisome smells, and her maids flee far from her and giggle in secret. But the tearful lover, denied entry, often smothers the threshhold with flowers and garlands, and anoints the haughty door-posts with marjoram, and plants his kisses, poor wretch, upon the doors; yet if, admitted at last, one single breath should meet him as he comes, he would seek some honest pretext to be gone, and the deep-drawn lament long-planned would fall idle, and then and there he would curse his folly, because he sees that he has assigned more to her than it is right to grant to any mortal. Nor is this unknown to our queens of love; nay the more are they at pains to hide all behind the scenes from those whom they wish to keep fettered in love; all for naught, since you can even so by thought bring it all to light and seek the cause of all this laughter, and if she is of a fair mind, and not spiteful, o’erlook faults in your turn, and pardon human weaknesses.