Ok thanks Daniel!

Posts by Cassius

-

-

Daniel have you put up a blog or website anywhere to organize the work you are producing?

-

This is a nicely done audiovisual but the message is hard to digest in any format!

-

-

Also:

- How did you get the forum post to provide only the title and hide the body til clicked? That is very useful?

- I don't have time to read the full essays at this moment but of course I applaud your efforts and hope you will expand them -- I certainly don't think there is only one approach and any efforts in any new direction are always appreciated.!

-

Daniel I have only started reading your posts but first -- it is good to see you again after such a long absence!!

-

Many good points in that article, but this is the heart of it and this is where it crashes and burns into stoicism / asceticism and the opposite of what Epicurus taught. Even before the article starts! Free ourselves of desire? Hardly! The issue is learning to pursue our desires with maximum net result, not "free ourselves of desire."

“I know not how to conceive the good, apart from the pleasures of taste, of sex, of sound, and the pleasures of beautiful form.” - Epicurus

-

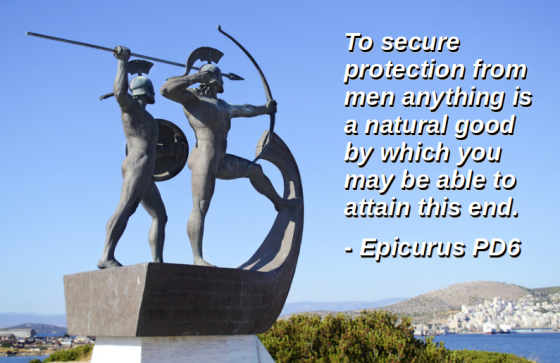

**Visualizing Principal Doctrine 7** This doctrine follows closely on the issue of self-protection presented in principal doctrine six, expanding it in an obvious direction while affirming that the ultimate test is always the result obtained, not conformity to an ideal:

"Some men wished to become famous and conspicuous, thinking that they would thus win for themselves safety from other men. Wherefore if the life of such men is safe, they have obtained the good which nature craves; but if it is not safe, they do not possess that for which they strove at first by the instinct of nature."

Epicurus had previously said: "To secure protection from men anything is a natural good by which you may be able to attain that end." "Anything" is a broad term, and would include even politics and dictatorships being natural goods - if they are successful. But we can't know in advance what the result of any one course will be. It is possible that we may pursue dictatorship or kingship and overcome all obstacles to success. If we do, and if we die in our sleep surrounded by friends after a long and happy life, then our pursuit of fame or kingship has proven to be an excellent course for us. In other words, if we succeed then we have achieved the goal for which we set out, regardless of the odds that seemed to be against us based on past experience.

But it is frequently the case that politics and dictatorship and kingship spur envy and ill will from other men. Whether that response is justified or not, it is frequently the case that dictators and kings meet a violent and unhappy end.

Both are true -- the generalization is valid as a generalization, but a generalization is not a guarantee that a choice will work out in every instance.

The point here is the same which is made throughout Epicurean texts: There is no fate, no divine creator, no realm of ideal forms which will inevitably lead certain choices to success or failure. The universe operates by natural principles, including the swerve in the atom, and we have freedom to influence some things in life, but not others.

The Epicurean message may seem scandalous to those who would prefer "justice" or "fairness" in the universe, but the message is clear, and it is consistent with what we actually observe. Some dictators / kings / famous people live long and happy lives after following paths that many would consider awful, while others who are paragons of morality crash and burn in the worst possible ways.

In an Epicurean universe we should not look for inevitable outcomes. We can estimate generalities and make predictions based on past experience, but the test of success is whether it in fact succeeds. There are no divine patterns which will always produce the happiest outcomes in life. If we wish to live happily we make our choices, we take our chances, and we work as diligently as possible for pleasurable living, always knowing that there are no guarantees in life except that it will eventually be over.

--------------------------

More graphics for Principal Doctrine 7 can be found here.

-

**Visualizing Principal Doctrine 6** This doctrine has some issues with translation, but in the end the meaning seems clear. The text which is generally reproduced today is that in the attached graphic: "To secure protection from men anything is a natural good by which you may be able to attain that end." I have retained that formulation in this graphic because I believe that this statement is accurate to the thrust of Epicurean philosophy.

As stated at Attalus.org and other authorities, the text from which translators work references kingship, and can be translated into English as

"In order to obtain security from other people, there was (always) the natural good of sovereignty and kingship, through which (someone) once could have accomplished this."

Apparently many authorities, including Usener and Bignone, believe that the explanation here is that the reference to kingship was just such a reference, made by someone in commenting on the text over the ages, which at some point crept into the text itself. This theory would be consistent with the statement made elsewhere in the Epicurean texts that "the wise man in an occasion, will serve even a king/monarch."

Be that as it may, the wider view that anything (and not just the assistance of kings) is a natural good when necessary to obtain safety from other men. This wider meaning without the reference to kingship is amply supportable by Epicurean philosophy. One such example in a text that survives intact is Torquatus' statement in On Ends:

"Yet nevertheless some men indulge without limit their avarice, ambition and love of power, lust, gluttony and those other desires, which ill-gotten gains can never diminish but rather must inflame the more; inasmuch that they appear proper subjects for restraint rather than for reformation."

The same view is also consistent with the last of the Principal Doctrines, PD40:

As many as possess the power to procure complete immunity from their neighbors, these also live most pleasantly with one another, since they have the most certain pledge of security, and after they have enjoyed the fullest intimacy, they do not lament the previous departure of a dead friend, as though he were to be pitied.

So whether the subject is kingship or any other defensive or preventatively offensive device, the wider meaning is clear:

"To secure protection from men anything is a natural good by which you may be able to attain that end."

--------------------------

More graphics for Principal Doctrine 6 can be found here.

-

This thread is for discussion of the FAQ entry found here.

-

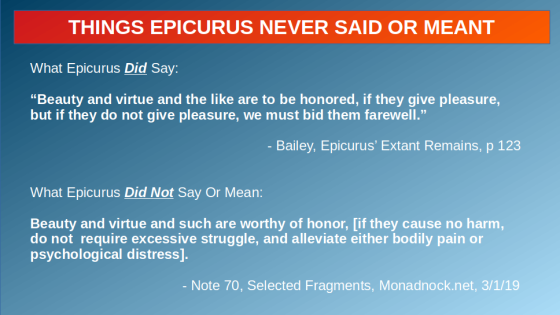

I noted this alleged limitation on what Epicurus meant by "pleasure" just this morning, and don't have the time to expand the argument beyond what is below. I have a lot of respect and appreciation for the author of the Monadnock website, but I think this alleged interpretation of "pleasure" in this fragment is a serious misinterpretation of the meaning. This is Stoic-influenced projection, and there is no way that ancient Epicureans would have accepted this understanding of what Epicurus was teaching, from the man who was famous for his candor, and who explicitly endorsed pleasure as normally understood rather than word games, and who said:

I know not how to conceive the good, apart from the pleasures of taste, of sex, of sound, and the pleasures of beautiful form.” - Diogenes LaertiusHe differs from the Cyrenaics with regard to pleasure. They do not include under the term the pleasure which is a state of rest, but only that which consists in motion. Epicurus admits both; also pleasure of mind as well as of body, as he states in his work On Choice and Avoidance and in that On the Ethical End, and in the first book of his work On Human Life and in the epistle to his philosopher friends in Mytilene. So also Diogenes in the seventeenth book of his Epilecta, and Metrodorus in his Timocrates, whose actual words are: “Thus Pleasure being conceived both as that species which consists in motion and that which is a state of rest.” The words of Epicurus in his work On Choice are : “Peace of mind and freedom from pain are pleasures which imply a state of rest; joy and delight are seen to consist in motion and activity.” - Diogenes Laertius

They affirm that there are two states of feeling, pleasure and pain, which arise in every animate being, and that the one is favorable and the other hostile to that being, and by their means choice and avoidance are determined; and that there are two kinds of inquiry, the one concerned with things, the other with nothing but words.

- Diogenes Laertius

Hence Epicurus refuses to admit any necessity for argument or discussion to prove that pleasure is desirable and pain to be avoided. These facts, be thinks, are perceived by the senses, as that fire is hot, snow white, honey sweet, none of which things need be proved by elaborate argument: it is enough merely to draw attention to them. (For there is a difference, he holds, between formal syllogistic proof of a thing and a mere notice or reminder: the former is the method for discovering abstruse and recondite truths, the latter for indicating facts that are obvious and evident.) Strip mankind of sensation, and nothing remains; it follows that Nature herself is the judge of that which is in accordance with or contrary to nature. What does Nature perceive or what does she judge of, beside pleasure and pain, to guide her actions of desire and of avoidance?

- Torquatus, In Cicero's On Ends

Source for the alleged limitation - see note to translation of fragment 70: http://monadnock.net/epicurus/fragments.html#n70

-

I was having a conversation with a friend about all this earlier today, and I realized something I should have seen years ago: probably the best way to start explaining the philosophy of Epicurus would be to show this video, and to also show two other videos, one from Timaeus on the nature of the universe as divine, and one from Philebus on Plato's objection to pleasure as the ultimate guide to life. That would provide a good foundation for then beginning to explain Epicurus' response in each of the three main areas of philosophy (epistemology, physics, and ethics). I wish there were equivalent videos on Timaeus and Philebus -- in the absence of them they will need to be created.

-

Has everyone here seen this? It is super-critical. If you haven't seen it, watch, and be revolted! (And better yet, revolt and join Epicurus!)

-

-

I am looking for a free usable PDF Greek-English dictionary for helping check basic words. I see this one on books google com and it appears to be the best I've come across so far, but I haven't checked Archive.org.

I respect the scholarship of older writers at least as much as I do the modern ones, so I would think anything published from 1800 to about 1950 would be very usable.

Does anyone have any suggestions? -

-

" ... there was an established tradition of reading Odysseus' professed appreciation of Phaeaciean pleasures as an Epicurean manifesto."

I maintain there is no telos more pleasing than when good cheer fills all the people, and guests sitting side by side throughout the halls listen to the bard, and the tables are loaded with bread and meat, and a steward drawing wine from the bowl brings it round to our cups. To my mind this (telos) is something most beautiful.

-

And this is exactly on point: There are times to celebrate richly, rather than simply:

-

The Epigrams of Philodemus: http://www.attalus.org/poetry/philodemus.html

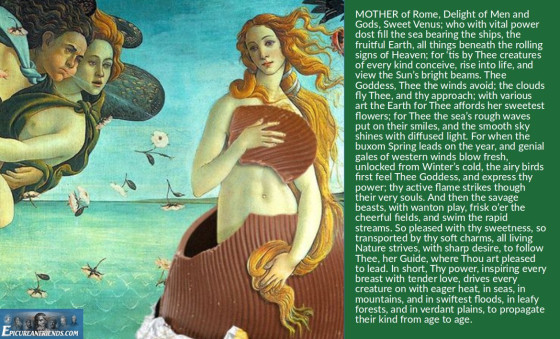

I particularly like the implications of this one, imagined to be said by Venus to humans who throw their lives away pursuing asceticism rather than pleasure. It mirrors several sayings including "30. Some men spend their whole life furnishing for themselves the things proper to life without realizing that at our birth each of us was poured a mortal brew to drink."

[5.306] { G-P 13 } GAddressed by a Girl to a Man

You weep, you speak in piteous accents, you look strangely at me, you are jealous, you touch me often and go on kissing me. That is like a lover ; but when I say "Here I am next you" and you dawdle, you have absolutely nothing of the lover in you.

-

If you can't walk and chew gum at the same time you aren't going to be a very successful human, and if you can't navigate between the extremes of asceticism and extravagance then you certainly aren't going to be a successful Epicurean.

So in that spirit if you can't consider the image of Venus with which Lucretius opened "On the Nature of Things," or of Aphrodite, the patron goddess of all those of ancient Greece who honored Pleasure, without tripping up on the perils of intoxicated hedonism, then you're not on your way toward understanding the ancient Epicurean elevation of Pleasure as the alpha and omega of the blessed life.

So here are a couple of artistic evocations of that understanding.

Philodemus:

Charito has completed sixty years,

but still black is her long wavy hair

and still upheld those white, marble cones of her bosom stand firm without encircling by brassiere.

And her skin without a wrinkle, still ambrosia,

still fascination, still distills ten thousand graces.

But you lovers who shrink not from fierce desires,

come hither, forgetting of her decades.

Finding Things At EpicureanFriends.com

Here is a list of suggested search strategies:

- Website Overview page - clickable links arrranged by cards.

- Forum Main Page - list of forums and subforums arranged by topic. Threads are posted according to relevant topics. The "Uncategorized subforum" contains threads which do not fall into any existing topic (also contains older "unfiled" threads which will soon be moved).

- Search Tool - icon is located on the top right of every page. Note that the search box asks you what section of the forum you'd like to search. If you don't know, select "Everywhere."

- Search By Key Tags - curated to show frequently-searched topics.

- Full Tag List - an alphabetical list of all tags.