I am pretty sure I did not see "Name of the Rose." Worth watching, or gag-inducing deference to the Vatican and "holiness" of the church (attributing anything bad to bad people as opposed to the rotten foundation)?

Posts by Cassius

-

-

Oh, too, there was an early church figure associated as being Epicurean too -- i forget the name - {Pelagius?} Might need a thread on him too.

-

Wasn't the whole secret hidden manuscript the plot of Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose?

You know a topic on the "Secrets of the Vatican" might make for an interesting thread itself. I've heard of that, but the only related them I am familiar with is that Tom Hanks movie -- what was that?

Does anyone have enough interest or material for a "Secrets of the Vatican" thread?

-

Getting back to Elli's post for just a moment, I think that it would be interesting to consider the possibilities of what was going on with Raphael drastically revising that particular figure, even if we assume Elli's contention is correct:

- the first that comes to mind is that it appears that the drawing was first conceived with someone else in that position. If so, then that observation would tend to diminish any linkeage between the other figures arrayed nearby with Elli's Epicurus. I think we had previously speculated that one of more of them might be female and perhaps a reference to Epicurus' associates, but that possibility might be less likely if the original drawing was not intended to be Epicurus, because those other figures remain the same.

- Can we tell anything of significance about the figure that was removed? His eyes seem strange to me. I wanted to describe it as a "deer in the headlights" look but that might not be best. Might be best to speculate about him based on his headpiece, which I don't recognize but which might be identifying.

- Then there's the dramatic change in the wreathed figure. That may say something too,

-

a significant work by an important figure was hidden away in perfect secrecy.

I grant you that it is a poor idea to impute efficiency to the core church leadership. However I don't hesitate for a moment to impute power-lust and corruption to them, so there's that aspect as well. And I am not sure that our alternatives are mutually incompatible - they apparently wrote over lots of early manuscripts and there could be some combination of issues - obviously Lucretius did escape their worst efforts, and apparently the works of Cicero and Diogenes Laertius were too widespread to be eliminated entirely.

The main part of this aspect that concerns me is that in my view I see over and over examples of where individual "rebels" get stamped out by the central orthodoxy, and the lesson I take from that is that no countervailing force can hope to succeed for long unless it too "organizes" so as to perpetuate itself. As brilliant as Epicurus was, his works barely survived, and then likely only because they penetrated the culture so far initially that the views were picked up by others elsewhere and perpetuated.

I'm no Nietzsche expert but my understanding is that a similar observation (that nature does not provide that the "strong" always survive over the "weak" who have superior numbers) was behind much of Nietzsche's critique of some of Darwin's views. Regardless of that, I don't think we should underestimate what Epicureans in history have always been up against, and I don't at all think that those forces of opposition are gone. In fact, I see them again, at present, gathering strength for another offensive.

-

Yes I am thinking that there are not a large number of podcasts dedicated to Epicurus or Lucretius, so we probably pop to the top of the list of podcast searches much more than general text searches at google and similar. Thanks for letting us know.

EDIT: I checked out ivoox to see how high we were, and I was struck that we weren't nearly as high as i thought. Had to get to page two before finding us. Not sure how their rankings work. But it looks like the number of episodes may work for us.

-

Consider first that neither the Vatican nor anyone else even knows what Jesus or ANY of his disciples looked like.

As for a likeness of Jesus and.or the disciples, I think the most likely answer to that is that he never really existed except as a composite figure of one of more various local rebellion-leaders.

As for Shakespeare I am tempted to think much the same thing as well.

And there certainly have been "good" figures mixed in to the history of the catholic church (and the rest of organized religion), but I don't see that really changing its overall picture as machinery for manipulation and oppression of the "masses."

-

Glad I could help Elli! I will never believe for a second that the Vatican ever lost track of the correct image of Epicurus. I will never believe for a second that the Vatican didn't keep in its records a complete copy of Lucretius' poem. I will never believe for a second that there aren't many more texts of Epicurus and the Epicureans secreted away in the Vatican Library even today.

The Vatican has always known, and some of us over the years have always known, that Epicurus was the Number One mortal enemy that the Church has had since its inception. Nietzsche saw it. Norman DeWitt was probably correct that the early Christians considered Epicurus either one of, or the main, "Anti-Christ." Talmudic scholars have always known it, using Epicurus' name as a term of denunciation. I don't know about the past Islamists, but I would certainly expect them to have seen the same thing.

This is something that is totally lost in discussing Epicurus as primarily interested in "pleasure," especially in the form of "absence of pain." Epicurus was a philosophical and moral revolutionary, and the various religious groups had to work to stamp him out because his comprehensive view of the universe and the place of humanity in it would blow their fantasies sky high if they became well known and accepted by significant numbers of people. It does a great disservice to Epicurus to focus on food and drink and bodily pleasures - there's no doubt in my mind but that Epicurus was aiming at a virtual overthrow of the established culture and education - the groups that adopted Christianity and Islam and (today) Humanism so completely. People who are focused on those issues won't ever see what a revolutionary Epicurus was.

I think a lot of people over history have seen and understood that, and the Vatican saw and understood it too. I would therefore expect that they studied their primary opponent in close detail and kept good records of how they planned to defeat his ideas and prevent their flaring up ever again.

And the primary way they did that was to multiply Cicero's characterization of Epicurus as effeminate (focused on sensual pleasure rather than seeing "feeling" as the philosophical opponent of Virtue and Religion. And that's the way they succeeded in branding his ideas as disreputable and unfit for discussion in the camp or in the Senate (the way I understand Cicero described it).

In fact that's the thought I woke up with this morning, and started to post about. I know in the past I've received some criticism for focusing on the importance of "pleasure" as the goal of life, and at this point I'll begin to agree with that criticism, at least to this extent: I don't think Epicurus saw his work on the practical side of pleasure (what to eat, drink, clothing, dance, etc) as particularly unique or what he wanted to be remembered for. I think Epicurus saw his achievement as his insight that pleasure is really feeling, and that it's feeling rather than virtue and religion and rationalism that life is all about. I think Epicurus saw his comprehensive view of the universe as natural, as eternal, as infinite, and that there are no such things as supernatural gods or life after death, as the key benefit of his philosophy. Yes pleasure is important, but it's third in line in the principal doctrines after the dogmatic assertions that there are no supernatural gods and there is no life after death. The place that pleasure holds derives from those insights, and that there are no ideal forms or anything magic about "logic" and rationalism, and it's on all of that where Epicurus departs from the prior consensus, not just in appreciating good food and drink.

The Vatican knows that. The Vatican knows that defining "epicurean" as pursuing fine wine and dining and the like is never going to be a threat to their empire. They don't really care even for that, and thus they promote Cicero's "absence of pain" viewpoint, but in reality its the rest of the philosophy that's the iceberg waiting to take out the Vatican's Titanic.

-

Elli I wonder if Takis included this cartoon draft in his analysis?

-

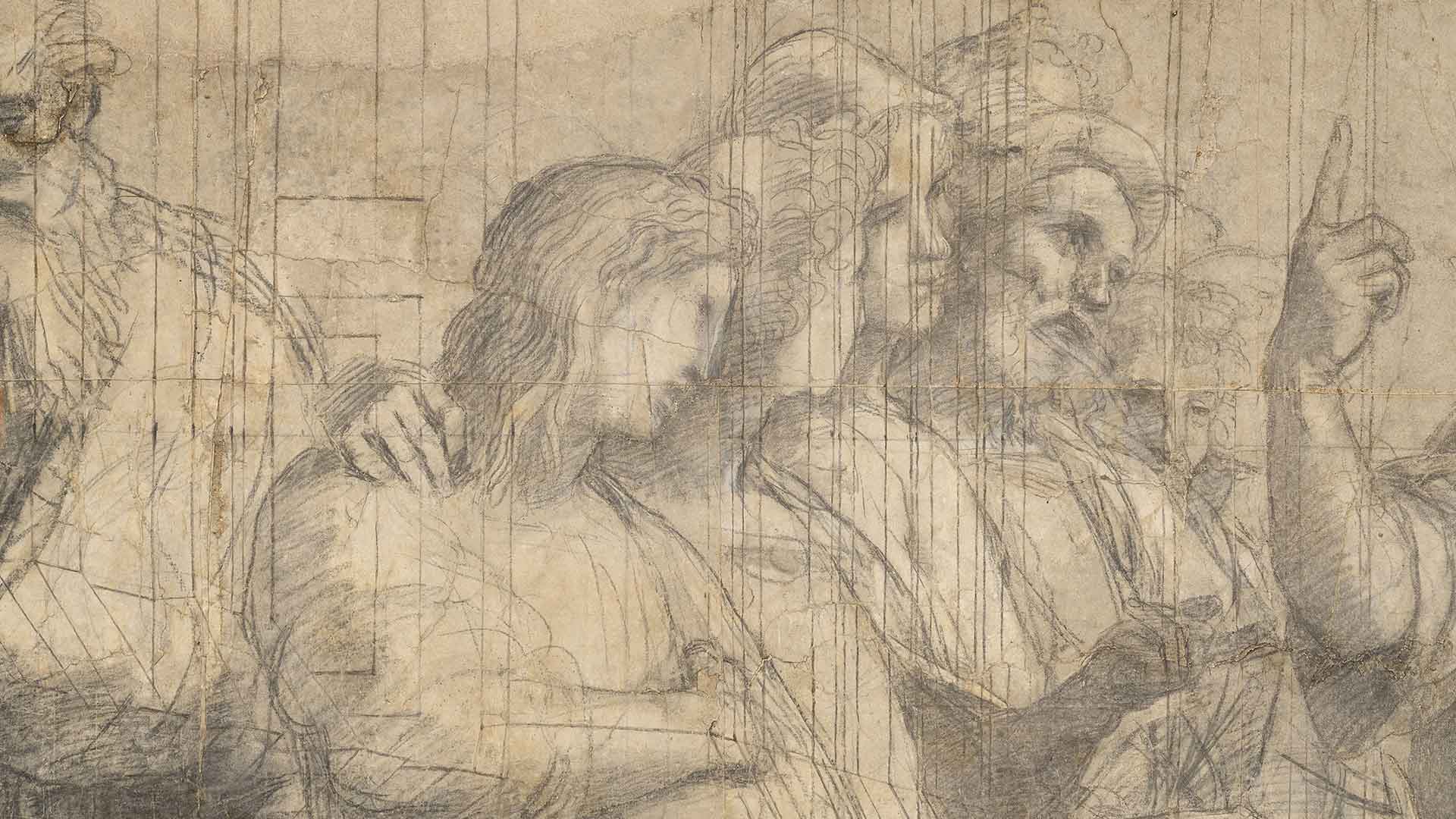

Closeup of the first draft of the section Elli is pointing to:

http://projects.mcah.columbia.edu/raphael/htm/ra…athens_draw.htm

also: https://www.ambrosiana.it/en/partecipa/p…chool-of-athen/

Does it not appear that the twisted-head figure has some kind of headpiece on? I would think that undercuts the idea that he was originally a major figure, and I would see his being replaced as some evidence of special attention being paid to this character. He may have a beard, but the overall look doesn't impress me as being a philosopher, unlike the figure that replaced him.

I'm not sure why but in the past (and some of my comments probably reflect this) I was thinking that this fresco was in some part of Italy other than the Vatican. Since I now stand corrected and find that this is in the Vatican, in my own mind that adds near-certainty to Elli's conclusion. I personally have no doubt that the arch-enemies of Epicurus in the Vatican never lost track of what their primary enemy looked like, and one of them could and would have pointed out his bust to Raphael.

-

-

I see one view of the cartoon is here: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/26/art…-of-athens.html

and indeed the area you are pointing to is different:As is the chubby wreathed figure:

My first impression is that these differences help your thesis, but that's only a first thought based on thinking that the preliminary sketch appears to be a generic set of onlookers with a man whose head is twisted as if he is paying particular attention or is otherwise an inferior student. On the other hand the finished product appears to be a dead ringer for Epicurus with much different head position and facial expression. I don't think you would insert someone strong like that (complete with philosopher beard) unless you wanted to feature a particularly important person.

If we could get a more clear view of that twisted head figure we might be able to learn more.

Also, the forerunner of the wreathed figure looks nothing like a Greek philosopher at all (nor does the current wreathed figure.)

-

Elli I see this section from the Wikipedia article but I have never seen pictures of any of these preliminary sketches. Have you found them and checked to see whether there are any details in the figures that would bear on your thesis?

-

I discovered your podcast by chance, just after exploring Lucretius' book.

I'm interested to know how you discovered it -- by using a podcast app to search for Lucretius, or what?

I don't feel confident to participate yet,

I think if you will look around you will see proof that everyone here is very nice and welcoming regardless of your level of knowledge. We've tried very hard to keep everything friendly and even "light" - at least where appropriate -- so if you experience any comments you feel are less than welcoming you let me know by private message and I'll take care of the offending party - but I am quite sure that isn't going to happen!

-

Welcome again Alex, and thanks for saying hello so quickly!

-

Hello and welcome to the forum Alex !

This is the place for students of Epicurus to coordinate their studies and work together to promote the philosophy of Epicurus. Please remember that all posting here is subject to our Community Standards / Rules of the Forum our Not Neo-Epicurean, But Epicurean and our Posting Policy statements and associated posts.

Please understand that the leaders of this forum are well aware that many fans of Epicurus may have sincerely-held views of what Epicurus taught that are incompatible with the purposes and standards of this forum. This forum is dedicated exclusively to the study and support of people who are committed to classical Epicurean views. As a result, this forum is not for people who seek to mix and match some Epicurean views with positions that are inherently inconsistent with the core teachings of Epicurus.

All of us who are here have arrived at our respect for Epicurus after long journeys through other philosophies, and we do not demand of others what we were not able to do ourselves. Epicurean philosophy is very different from other viewpoints, and it takes time to understand how deep those differences really are. That's why we have membership levels here at the forum which allow for new participants to discuss and develop their own learning, but it's also why we have standards that will lead in some cases to arguments being limited, and even participants being removed, when the purposes of the community require it. Epicurean philosophy is not inherently democratic, or committed to unlimited free speech, or devoted to any other form of organization other than the pursuit by our community of happy living through the principles of Epicurean philosophy.

One way you can be most assured of your time here being productive is to tell us a little about yourself and personal your background in reading Epicurean texts. It would also be helpful if you could tell us how you found this forum, and any particular areas of interest that you have which would help us make sure that your questions and thoughts are addressed.

In that regard we have found over the years that there are a number of key texts and references which most all serious students of Epicurus will want to read and evaluate for themselves. Those include the following.

- "Epicurus and His Philosophy" by Norman DeWitt

- "A Few Days In Athens" by Frances Wright

- The Biography of Epicurus by Diogenes Laertius. This includes the surviving letters of Epicurus, including those to Herodotus, Pythocles, and Menoeceus.

- "On The Nature of Things" - by Lucretius (a poetic abridgement of Epicurus' "On Nature"

- "Epicurus on Pleasure" - By Boris Nikolsky

- The chapters on Epicurus in Gosling and Taylor's "The Greeks On Pleasure."

- Cicero's "On Ends" - Torquatus Section

- Cicero's "On The Nature of the Gods" - Velleius Section

- The Inscription of Diogenes of Oinoanda - Martin Ferguson Smith translation

- A Few Days In Athens" - Frances Wright

- Lucian Core Texts on Epicurus: (1) Alexander the Oracle-Monger, (2) Hermotimus

- Philodemus "On Methods of Inference" (De Lacy version, including his appendix on relationship of Epicurean canon to Aristotle and other Greeks)

It is by no means essential or required that you have read these texts before participating in the forum, but your understanding of Epicurus will be much enhanced the more of these you have read.

And time has also indicated to us that if you can find the time to read one book which will best explain classical Epicurean philosophy, as opposed to most modern "eclectic" interpretations of Epicurus, that book is Norman DeWitt's Epicurus And His Philosophy.

Welcome to the forum!

-

Sounds like perhaps for practical purposes the 20th of January each year might serve as a reasonable approximation, if someone were looking for a stable date.

-

-

-

The oldest Lucretius (or other book) I have is the John Mason Goode edition from 1805. I have it in a glass case, but I fear you are right that humidity is a big enemy. Let us know what you find out as to how to keep it safe.

Finding Things At EpicureanFriends.com

Here is a list of suggested search strategies:

- Website Overview page - clickable links arrranged by cards.

- Forum Main Page - list of forums and subforums arranged by topic. Threads are posted according to relevant topics. The "Uncategorized subforum" contains threads which do not fall into any existing topic (also contains older "unfiled" threads which will soon be moved).

- Search Tool - icon is located on the top right of every page. Note that the search box asks you what section of the forum you'd like to search. If you don't know, select "Everywhere."

- Search By Key Tags - curated to show frequently-searched topics.

- Full Tag List - an alphabetical list of all tags.